End-of-Life Bowel Care

Patients in palliative care experience a myriad of complex physical and emotional issues, but there is one which is often overlooked: end-of-life bowel management. During this difficult time, caregivers want to do everything they can to help patients maintain comfort and dignity, and bowel care plays an important role in this.

Eighteen percent of palliative care patients experience bowel pattern changes, rising to 80% for end-of-life patients, particularly when opioid pain medication is involved.1,2 It’s essential to create a proactive bowel management program to help prevent and alleviate the discomfort of palliative patient incontinence, impaction, and constipation.

Palliative Care Bowel Care Assessment

Assessments for palliative bowel care should include:

- frequency of bowel movement

- stool color and consistency

- amount of stool

- what triggers a bowel movement

- whether the patient is experiencing discomfort (like abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, or straining)

- how diet impacts bowel movements

- educating the patient about the benefits of an effective bowel care management program

In the absence of any oral intake, the body still produces 1 to 2 ounces of stool per day, so even patients who are no longer eating or drinking should have a bowel movement every three days. For comatose patients, an abdominal and bowel assessment should be performed to ensure they are having appropriate bowel movements.

Bowel Care Management During Palliative Care

After performing a thorough assessment of a patient’s bowel care needs, health conditions, and medications, it’s important to establish and maintain a consistent bowel care routine to minimize complications.

Predictability improves quality of life and reduces pain/discomfort. Establish a bowel routine that follows a patient’s typical bowel patterns. First thing in the morning, before bed, and approximately 30-40 minutes following a meal are common times for bowel care.

Getting out of bed, if possible, can help prompt the urge to have a bowel movement. Patients should not resist the urge to pass stool which can lead to constipation.

Continue to evaluate the effectiveness of bowel care management and make adjustments as needed, but give any change some time to work, including medication changes.

Constipation and End-of-Life Care

There are several things to consider when a palliative care patient is experiencing constipation, including:

Health Conditions: evaluate any underlying medical conditions which could be causing or exacerbating constipation, such as a GI obstruction, tumor, depression, or radiation fibrosis.

Pharmaceuticals: Opioids are the primary cause of constipation for end of life care. All medications should be evaluated as anticholinergics, sedatives, antidepressants, diuretics, and other medications can have constipation as a side effect.

Metabolic changes: dehydration, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia can cause or worsen constipation.

Neurologic changes: conditions like cerebral tumors, spinal cord injury/illness, autonomic failure, and ALS also affect bowel movements.

Lifestyle changes: advanced age, reduced activity, diet changes (such as decreased fiber intake), decreased fluid intake, and social impediments also contribute to a patient’s bowel care needs.

Non-Pharmacological Bowel Care Treatment

Before exploring pharmacological treatment for bowel care, it’s important to ensure that all non-pharmacological elements of bowel care are in place, including adequate fluid intake, appropriate level of dietary fiber, fruit laxatives (such as prunes, dates, figs, and raisins), and a regular toileting routine.

Pharmacological Bowel Care Treatment

There are several different categories of laxatives. Some work on stool, some on the intestine, and others work on both. Every patient has different laxative needs, but all are employed to relieve constipation:

- Emollient Stool Softeners: Emollient laxatives contain the active ingredients docusate sodium and docusate calcium. Stool softeners work by hydrating and softening stool, making it easier to pass, and are considered to be gentle and well-tolerated.

- Lubricant: Lubricant laxatives contain mineral oil, which coats stool to help it move more easily through the intestine, and also coats the intestines to help prevent water loss from the stool. Mineral oil is not for use on a regular basis.

- Bulking Forming: Bulk forming laxatives contain the active ingredients psyllium, methylcellulose, and calcium polycarbophil, and work by forming a gel in the stool that helps it hold more water. Stool increases in volume as a result, triggering the intestine to pass stool more quickly.

- Hyperosmotic Laxatives: hyperosmotic laxatives contain the active ingredients polyethylene glycol and glycerin, which draw more water into the intestines. This helps soften stool to help it move more easily through the intestinal tract.

- Saline Laxatives: Saline Laxatives contain the active ingredients magnesium citrate and magnesium hydroxide, which draws more water into the intestine, softening stool and stimulating movement in the intestines. Saline laxatives should not be used on a regular basis. When used regularly, they can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.

- Stimulant Laxative: Stimulant laxatives contain the active ingredients such as bisacodyl or sennosides, and work by stimulating the bowel and increasing movement in the intestines. Despite the quicker results, stimulant laxatives come with many unpleasant side effects and should not be used on a regular basis as they can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, bloating, gas, and abdominal pain.

Keys to a Successful End-of-Life Bowel Management Program

There are five primary components of a successful end-of-life bowel management program:

- Effective, proactive, and consistent bowel management is essential to make palliative care more comfortable and dignifying for patients and families.

- Establish a protocol for everyone responsible for the patient’s care and educate and inform the patient, family, and caregiver(s) about the importance of following bowel care protocols and assessments.

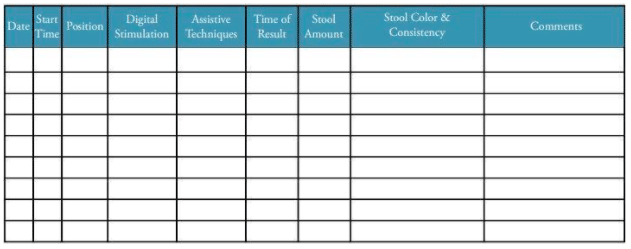

- Keep a daily bowel chart that tracks bowel movement timing, appearance, and amount.

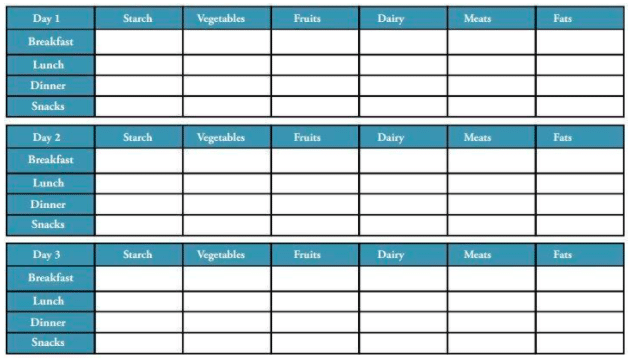

- Keep a daily dietary chart to track all food and fluid intake.

- When a patient is experiencing stress and/or discomfort, consider bowel management as a potential source. Some patients and families are reluctant to discuss bowel issues, so they may have to be prompted. Continue to listen, provide feedback, inform, and educate on the importance of bowel care at the end of life.

Examples of Dietary and Bowel Charts:

Bowel Chart:

Dietary Chart:

Enemeez® Mini-Enemas

The Enemeez® formulation is a hyperosmotic, stool-softening laxative that works by drawing water into the bowel from surrounding body tissues. The docusate sodium in this mini enema product prepares the stool to readily mix with watery fluids. It softens and loosens stool and initiates a normal, replicated bowel movement, typically within 2-15 minutes.

Enemeez® Plus is the same formulation as Enemeez®, with the addition of 20mg of benzocaine, assisting in the anesthetization of the rectum and lower bowel. This formulation was developed for patients who experience autonomic dysreflexia, hemorrhoids, fissures, or painful bowel movements.

Request Samples or Educational In-Service

Get started with a sample request or In-Service for your facility today. Request samples here or an educational In-Service here.

Disclaimer: The material contained is for reference purposes only. Quest Products, LLC does not assume responsibility for patient care. Consult a physician prior to use. Copyright 2021 Quest Products, LLC.

Sources:

- Carter B, Black F, Downing GM. Bowel Care – Constipation and Diarrhea. In: Downing GM, Wainwright W, editors.Medical Care of the Dying. Victoria, B.C. Canada: Victoria Hospice Society Learning Centre for Palliative Care; 2006. p. 341-62.

- McMillan SC. Presence and severity of constipation in hospice patients with advanced cancer. American Journalof Hospiceand Palliative Care. 2002November/December 2002;19(6):426-30.

- Hospice and Palliative Care: Constipation & Incontinence, Christine Hogan, RN, BSN, CRRN